This is a rather long review of a book which is not old, or fiction or children's. It's a nonfiction book from 2013 about the origins of a racehorse rescue, CANTER, and the tragedy that led to its founding. The author's frankness about the guilt, lingering and permanent, over the choices she made with her horses and her family, makes for powerful reading.

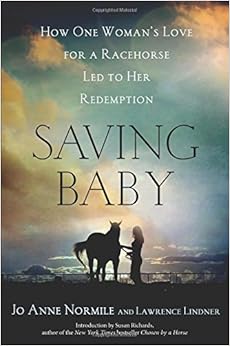

Saving Baby: How One Woman’s Love For A Racehorse Led To Her

Redemption

Jo Anne Normile and Lawrence Lindner

2013, St. Martin’s Press

In 1973, a young Jo Anne Normile fell in love with a

racehorse. Secretariat did that to

people. His stretch run in the Belmont Stakes

still makes your breath catch. Roughly 20 years later, the adult Normile leases

a pregnant Thoroughbred broodmare, exchanging the mare’s care during foaling

for the right to the next breeding, which she plans to be to a Secretariat son. She doesn’t expect to fall in love with the

foal, who is technically supposed to be delivered back to the mare’s owner once

weaned. Then the foal is born.

At the sound of the

whicker, the baby lifted its head, its ears flopped to the side. It then let

out a whiny, although it was more like the honk of a Canadian goose, and that,

combined with our relief, I think, made all of us laugh hard.

Normile delights in the foal, Baby, doing all the ground

work that will make him calm, confident, easy to handle.

… I was determined

that Baby was going to grow to adulthood strong not just in body but also in mind

so that nothing would ever hurt him.

Inevitably, she and her husband decide to buy the colt. The owner agrees, but on condition they race

him. Nervous but willing, they embark on

a career as racehorse owners. First Baby and then Scarlett (their Secretariat

filly, born of the second breeding), head off to trainers.

Normile finds the racing world fascinating, and quickly

becomes very involved. She makes

mistakes with trainers, picks up the lingo, and learns more than she’d like

about abusive horsemen. Bad things

happen, but never quite bad enough to discourage her completely. In some of the best passages, she and

co-author Lindner show how the creeping sense of something wrong begins to live

in the back of her mind. She rationalizes the injuries and questionable

training practices, knowing that all competitive athletics requires risk of

pain and harm. She worries about her

horses, changing barns and trainers repeatedly until they get a trainer she

trusts and a barn setup more natural than the average. She learns of ‘breakdowns’

and why a big truck regularly rumbles by on its way to the empty fields behind

the track – it’s the company that picks up dead horses to take to the renderer.

The gruesome knowledge bothers her, but she feels safe in

that Baby and Scarlett are so lovingly tended and sound; the breakdowns are,

she thinks, mostly due to badly conditioned or lame horses being run with

injuries. And their first, hard-won, win

is intoxicating:

If I was hooked

before, even with the sinister goings-on that I had seen at the track, I was

addicted now… all the glamour of racing, of the Sport of Kings – it was

something I was now truly part of.

And then it all changes. Baby breaks down in a race, a single step that torques his

leg, shatters his tibia, destroys any hope of saving him. Normile ends up in

those empty fields with her horse, crying and telling him she’s sorry, so

sorry, that she failed him, and then has to step back for the vet to euthanize

him.

Normile sets out to get the track, whose surface was being

decried as dangerous before that fatal race, redone. In the process, she discovers the even more gruesome

fate of racehorses who either break down without dying outright, or simply aren’t

working out at racing. They’re sold for

meat. Worse than that, the processing of

horses for meat is brutal – they’re crammed into trucks without food, water

or - when they’re injured – painkillers.

The trucks are often designed for much shorter cattle, so the horses are

cramped and bent over for the long ride to the slaughterhouse. The slaughter

method is inexact, a bolt to the brain that often misses the agitated horse,

and has to be repeated. Horrified at

this new face of racing, so far removed from the glory of Secretariat’s career

or the joy of watching Baby run, Normile launches a rescue for racehorses.

It’s useful at this point to remind yourself this was the

1990s. The nascent internet was the

exclusive property of a few tech geeks and the military. The racing industry’s

solution to slow or lame racehorses was still its dirty little secret, and secrets

were much easier to keep. And animal rescue had not yet exploded. Normile's efforts are all the more impressive.

Normile’s rescue is eventually name Communication Alliance

to Network Ex-Racehorses – CANTER. It

begins in Normile’s home state of Michigan, but spins off regional

organizations all over the U.S. Normile eventually steps away from CANTER to focus on her

family, as her husband has severe health issues. She is now involved with

another charity, Saving Baby Equine Chariy, whose mission is:

dedicated to

protecting horses, ponies, mules, and donkeys from slaughter, abuse and

neglect; promoting change through public awareness and education; rescuing

these animals in emergency situations; and providing financial assistance to

approved 501 (c) (3) organizations that rescue them from slaughter, abuse or

neglect in order to help as many as possible.

Brief review

A very polished, professional, well-executed book which hits very hard in the repeated passages about Normile's feelings of having failed her horses and how her attempts to make things right never quite do.

Interesting note:

The book was originally self-published, got good reviews, and was picked up by St. Martin's and re-issued in hardcover. (Original paperback cover below)

Personal note:

Around

2008, I happily followed two CANTER Mid-Atlantic bloggers who were retraining

racehorses for new homes. They were

lovely blogs.

Links